Is Extra Time Extra?

With the emphasis on standardized testing in today’s college process, extra time has moved to the forefront of academic controversies. The well-intended idea behind extra time is to level the playing field for all students. A student who is quite intelligent but who may have a disability that could hinder academic performance might never reach his or her maximum potential, and extra time tries to prevent this from happening.

The Americans with Disabilities Act, passed in 1990, prohibits marginalizing anyone based on a physical limitation. According to adata.org, Title III of the Act focuses on public accommodations and mandates a certain amount of compliance to make public facilities accessible to people even with disabilities. This even includes private businesses, directing them to make “reasonable modifications” to their practices to help serve the disabled. The College Board and other standardized testing agencies are included under this act, and thus extended-time accommodations are a way of catering to students with any kind of disability.

According to Ms. Deborah Biegen, Director of Ramaz’s Learning Center, it was indeed the ADA that set a precedent for providing extra time. Prior to the passage of the ADA, learning disabilities “weren’t something people necessarily talked about.” Awareness has been growing ever since then, which may be one of the reasons why the number of students receiving extended time seems to be increasing every year.

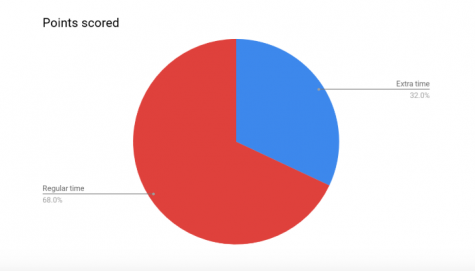

Ms. Biegen claims that Ramaz’s rate of extended-time testing is right on par with the national level, which is currently at about 20-25%. A recent survey of the Ramaz student body indicates a slightly higher percentage. Out of 100 responses, 32 people wrote that they do have extra time, which is 32%. The percentage of extra time recipients likely peaks in high school because that is when testing begins to “count” in a more formalized manner, and students and parents may become more aware of academic difficulties or disabilities. This is why extra time is sometimes given informally in middle school, often with a less rigorous vetting process than in high school. Extra time also can continue into college, though presumably with a testing update.

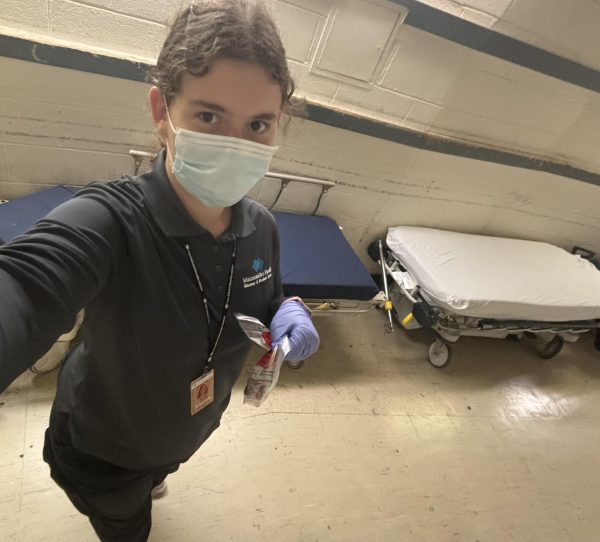

Ramaz, as a private school, has more control over which requests for extra time it approves. According to Ms. Biegen, the process is as follows: parents first submit a psychoeducational evaluation to the learning center, the learning center reads the evaluations and gets references and data from the student’s teachers, and then the learning center either accepts or rejects the request. Students applying for extra time usually have a learning, physical, or psychological issue. Items under the learning category include but are not limited to ADHD, dyslexia, and processing issues. Physical issues often result in stop-and-start testing – for example, if a student has diabetes, he or she may need to stop and refill insulin or have a snack in the middle of a test, or if a student has arthritis, the student may need to give his or her hands a rest. Personal crises that may prove a distraction and testing anxiety (although extra time for this is rarer) fall under the category of psychological issues. Some students will receive extra time on longer tests, such as final exams and SATs or ACTs. These students, notes Ms. Biegen, need the accommodation because the test is lengthier. They might be able to concentrate for a short forty-minute period, but sitting for two or more hours, as students may have to during final exams at Ramaz and during standardized tests, can prove to be more of a challenge to their focusing skills. Regardless of the reason for the accommodation, testing updates are required every three to four years in order for a student to continue receiving extra time.

When asked why they receive extra time, many students wrote that the reason they need it is that they are very slow test takers. Several students listed ADHD or a non-academic medical condition. “I’m diabetic, so if my blood sugar goes high or low, I need to stop,” answered an anonymous student. “The amount of time I stop I get back.” A second student said, “I’m a slow writer and reader, and sometimes when there are very long answers required my hand begins to hurt and I need to take like a 30-second break.”

Other students’ reasons revolved more around time challenges. “I was doing terribly on tests without extra time, because I was not finishing them and pages of the test were left completely blank,” said one student. Another said, “I seriously could not finish sections in time, because I was so anxious about the clock. I never finished a math or science section in even double time.” A third student added, “Thinking about my answer and outlining it in my head first takes me a lot of time. Sometimes it also takes a while for me to recall information.”

Some people in and out of Ramaz speculate that extra time is a money-oriented phenomenon, as testing for extra time is quite costly. There is tremendous pressure on doctors, who are paid a hefty sum, to approve all requests no matter how valid they may or may not be. Ms. Biegen refutes that assertion, saying, “Private testers do cost [a lot of] money, but there are clinics where a graduate student will do it for a much cheaper fee. The Board of Education will also test.” As one counter-example to Ms. Biegen’s statement, though, an anonymous student wrote, “I really need it [extra time] because of my extreme emotional and anxiety issues, such as manic depression and other disorders, but it is far too expensive to get tested for. And I find that I would do much better with it.”

A solution posed by Ms. Miriam Krupka, Dean Faculty, is having one psychologist in contract with the school. Anyone who requests extra time would be required to get a doctor’s note through that particular doctor so that families would not gravitate towards certain professionals who are more likely to provide the results parents and students want.

Aside from potential abuse of the policy, there remains a more fundamental criticism of extra time. Supposedly, the goal high school and college is not only to educate but also to prepare students to be professionals. Is it not better to help students cope with their academic issues, whether they be time or anxiety related or not, rather than giving them extra time? A doctor in an operating room doesn’t get extra time to help someone who has just suffered a heart attack and whose life is on the line.

The truth is that whether test-taking struggles actually translate to a professional environment or are just unique to test taking itself is still to be determined. Ms. Biegen emphasized that the ultimate goal is to eventually phase out of extra time, and some students find they no longer need it once they reach college, while others continue to use it in their higher education. However, Ms. Biegen mentioned that this idea of not having extra time later on in life as doctors, lawyers, teachers et cetera is something hotly debated by learning specialists at academic conferences to this day.

To combat those who claim extra time is unfair, Ms. Biegen talked about the experiences of her own children. “One of my daughters tried taking the ACT [reading] with time and a half and actually did worse…the point is, it won’t really help you if you don’t need it,” she said. “We do our best to make sure everyone who does need it is [accommodated].” More generally, extra time would not help a student who does not know the material, because no matter how much time the student has, he or she will not be able to figure out the answer.

One solution to the extra time conundrum is making sure that tests are less time dependent and more about knowing and analyzing the material. Unfortunately, at Ramaz, sometimes tests can be about how quickly a student can spit back everything he or she knows. “Without it [extra time], I’m always rushing, and on finals especially teachers try to cram in all the material at the end, so there is a ton on the tests, and they [teachers] don’t account for time,” wrote one student. Hadley Kauvar ’19 said, “I’ve had some math teachers who would just have you spit back the material, and I’ve had some who make you actually analyze [what] you’re learning.”

Some teachers of today, both at high-school and university levels, have taken strides to ensure that no student is disadvantaged who does or doesn’t have extra time. History tends to be one of those subjects that calls for scribbling down everything you know about a particular topic on a page, with students often filling up multiple blue books for history exams. As history department chair, Dr. Jucovy has moved away in the past few years from tests that depend heavily on rote memorization and more towards tests that require analytic thinking and application of knowledge. “The problem in testing in a different kind of way is how you still make sure that students have a sufficient amount of knowledge and analytical skills. There has to be a balance,” he said. Dr. Jucovy nonetheless operates under the assumption that if two students are taking an exam and one has forty minutes while the other is granted sixty, the second student needs that time. He defers to education specialists to determine whether or not that is the case.

“Before the extra time era, it was taken for granted that you had to be fast to do well in a quantitative subject. Tests were long, so you were really graded on how quickly you could do your work,” said a Columbia professor. “We [teachers] are more aware that that’s not necessarily a good way to grade students. We’re more conscious of not making tests too long so that points are taken off for actually getting things wrong and not just not finishing the test.”

Professor James Kahn (father of the author), department chair of economics at Yeshiva University, said, “For my tests, extra time isn’t much of a factor, because the tests don’t depend so much on speed. Either you know the material, or you don’t.”

Inside Ramaz and out, even in the college sphere, extra time has raised important educational questions. Hopefully, in the long run, it can be used as a tool that will not only make sure everyone has an equal opportunity on tests – ensuring that everyone who has extra time needs it and everyone who needs it has it – but will also allow educators to rethink their testing styles in a way that would be more beneficial to all students.

Natalie Kahn joined The Rampage staff as a freshman and wrote numerous articles before becoming Co Editor-in-chief this year. Natalie is a skilled writer...