Difficulties of Day School Davening

In a constantly-changing Ramaz schedule, from M day to C day to F day, one thing remains the same: the first 50+ minutes of the day are reserved for davening. These minutes are an important part of school culture, and members of the Ramaz Upper School community have strong and varied opinions about how the time should be spent. This article aims to uncover those opinions from both the student perspective—largely based on an anonymous poll that 70 students filled out—and the faculty perspective, based on interviews with several faculty members who daven with Ramaz students.

Davening: In school vs out of school

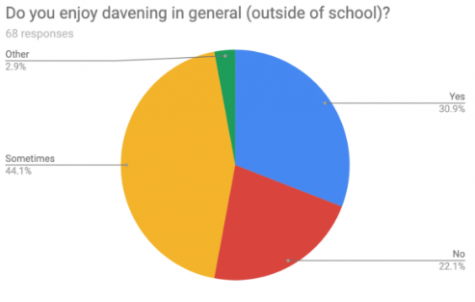

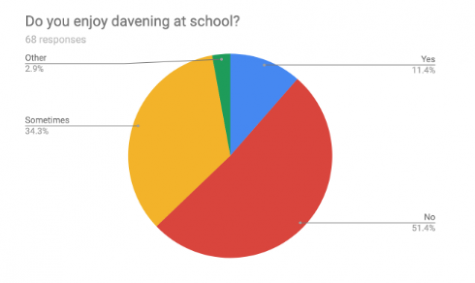

Based on the results of the poll, there is a large gap between the number of students who enjoy davening in general and the number of students who enjoy davening at school. Of the 68 responses to the question “Do you enjoy davening in general (outside of school)?” 31% of students responded in the affirmative, 22% answered no, and 44% said sometimes. However, when the question was changed to whether students enjoyed davening at school in particular, only 11% said yes (a 20% decrease), 51% said no (a 29% increase), and 34% said sometimes (a 10% decrease).

Students described several reasons that they prefer davening outside of school, primarily citing two problems with school davening: first, a feeling of being policed by the teachers, and second, a sense of exhaustion so early in the morning after long days studying and commuting.

To illustrate the first point, one student brought an analogy, suggesting that “school davening feels kind of like being an animal in a zoo, where the teachers are the zookeepers and the students are a wild herd. Some students sleep, some are trying to escape, and others are communicating through words and gestures.”

Throughout the survey, there was widespread agreement that the teachers who are present at davening “are policing, not davening,” which creates an unpleasant environment. “Praying is a very special and private activity,” said one student, “In school, it is just as meaningful…however, [it’s] harder to concentrate with teachers hovering over you to make sure you’re not talking.”

However, despite many students’ negative attitudes toward school davening, lots of students described meaningful relationships with davening outside of a school context. “I do find [davening] meaningful, and it provides a sense of comfort in knowing that there is some other force in the universe that can help me with my life,” wrote a student who described school davening, in contrast, as “forced down our throats.”

Despite this perception by students, teachers are working extremely hard not to “police” the davening. “My goal is not to force people to daven,” said Ms. Senders, who davens with the freshman minyan every morning, but rather “to facilitate a comfortable and growth-oriented environment for people to use as a point of connection or a point of reflection. I’m going to ask you to respect the process—when we’re standing, you’re standing; when we’re sitting, you’re sitting—but you don’t need to say a single word if you don’t want to.”

Ms. Krupka’s attitude toward appropriate behavior during davening is that “if you wouldn’t do it if you go to church with a friend, don’t do it here.” She describes a scenario in which a religious Catholic friend invites you to church, and everyone else in church stands up to sing a hymn you don’t know. Of course, you would stand up, too. “Treat the surroundings with the basic decency that [they] deserve, even if it’s difficult,” said Ms. Krupka.

As for the question of sleep, students complained that expecting full participation at 8am is simply unrealistic. “I never talk in davening because it’s disrespectful,” said one student, “but in my opinion, after the hours that I’ve had to keep in order to do well in school, falling asleep at 8am is not unjustified.”

On the flip side, some students do enjoy school davening. “I enjoy doing a mitzvah,” said one student. At school davening, “I can connect with Hashem and start my day off well,” wrote another. “I like the time in the morning to reflect,” said a third.

However, perhaps whether or not students enjoy davening isn’t the most important question. “It’s important to get our students to a place where they understand that tefillah is an important part of our day regardless of whether they’re connecting to it that day or not,” said Ms. Senders. “It’s not just an option or a means of connection—it’s written into our tradition. We are a link in the chain, and we can’t be the part of the chain that just breaks.”

What do students do during davening?

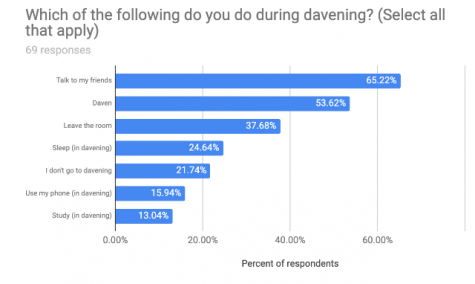

When students were asked to select all of the things they do during davening on a regular basis, the largest group (65% of respondents) indicated that they talk to their friends, followed by davening (53% of respondents) and leaving the room (38% of respondents). Students largely commented that they daven the amida, and many also added that they say Shema, but they tend to talk, space out, or leave the room during chazarat hashatz, Torah reading, and the rest of davening. Some students said that if they’re especially tired, they’ll sleep, or if they have a big test that day, they’ll study. “There are enough kids there that we can literally almost have a minyan in the bathroom also,” commented one student.

However, several teachers commented that these aren’t issues that are unique to Ramaz davening. “In both shul and school, there’s a big social dynamic,” said Rabbi Schiowitz, describing both school and shul davening as times when the community comes together, leading to a lot of talking and catching up.

“I don’t think there’s anything going on in our tefillah that is worse than what happens in most people’s normal tefillot on Shabbat morning,” said Ms. Krupka, “If anything we’re better—most people come on time. Almost no one is walking into shul before 10 am in most of these minyanim. I don’t think there’s any deep disrespect of tefillah going on. I think the weak parts of our davening are not just about Ramaz davening, but about prayer in general. I think there is actually a kol tefillah in that room.”

Skipping Davening

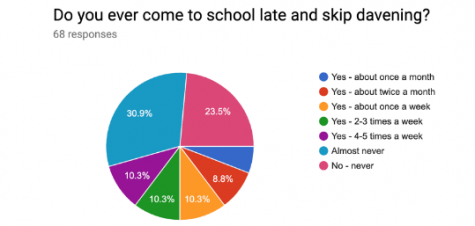

Of the 68 student responses to a poll question about skipping davening, 55% of students never or almost never skip davening, 25% skip davening once a week or less often, and 20% skip davening more than once a week. When asked why they skip davening, the most common answer was “sleep.” Some students choose to sleep in through davening because they’re too tired to wake up, but for some, it’s not a conscious choice—they simply oversleep because of exhaustion.

“If I come to school late, it’s because I had a late night,” said one student, “but instead of going to class first period, I daven instead.” For seniors, not having class first period is another reason to sleep late.

A few students commented that they skip davening because of work, doctors’ appointments, or because “davening is boring,” but the prevailing sentiment wasn’t a malicious one; after long days filled with extracurriculars, long commutes, and hours of homework, students are simply too tired to drag themselves out of bed in order to be at school in time for davening every single morning.

Special Minyanim

Outside of the daily grade-wide Ashkenazi minyanim and schoolwide Sephardi Minyan, there are minyanim that meet less frequently. Once a week, some students attend singing minyan, and twice a week, some girls attend women’s tefillah.

To explain why they attend singing minyan, students described it as “chill and more flexible,” having “more ruach,” as well as “more exciting/alive” and “a calmer environment that’s very intimate. Rabbi Weiser is phenomenal at that.”

As for women’s tefillah, the predominant reason that girls attend is the chance to participate more in davening. “The atmosphere is much more friendly and open, and I feel much more involved than I do in regular minyan,” said one girl. “It’s genuinely easier for me to pray there, even if it is only because it is a smaller group,” said another, “I find that even though I have friends in women’s tefillah, I talk less there than in my regular minyan.”

Eighteen students answered a question about what other special minyanim they would like to have. The most common suggestion was a meditation minyan (suggested by 4 students), followed by an extra-fast minyan (2 suggestions) and a partnership minyan (2 suggestions). Other students suggested a silent minyan where students daven on their own, an “exploratory/reflection minyan,” and “an entirely kid-led minyan with people who seriously want to daven.”

According to Ms. Krupka, Ramaz has considered or tried many different minyanim over the years. At one point, Ms. Krupka tried having davening in smaller groups of about 30 in classrooms, but this initiative wasn’t successful. It was too difficult to get a minyan right away, there was too much talking, and it was more distracting. Ms. Krupka also tried putting up quotes and pictures on the smartboards to help improve people’s tefillot, but she didn’t find that students thought it was helpful.

Furthermore, attempts to enhance student kavanah with special minyanim also come at a cost. “You’ve achieved one thing at the expense of another,” explains Ms. Krupka. First of all, she explains, students who participate in yoga, mediation, or discussion minyan haven’t actually fulfilled their basic requirement of minyan for the day. Second, without the regular minyanim, students lose the basic tefillah literacy that they gain from school davening, that “you’re familiar and comfortable with the ritual of a basic formula of prayer,” says Ms. Krupka.

Improving Ramaz Davening

When asked how to improve Ramaz davening, students responded in often-contradictory ways. Some students requested faster minyanim with fewer speeches. However, other students requested more opportunities to learn about the prayers and more singing. In line with both of these approaches, one student wanted more options and the opportunity to choose between minyanim.

Another paradox falls between one request that teachers are less strict and “treat it like a real shul” rather than “policing and walking around the aisles to make sure no one is speaking a word” and other students who want there to be less talking and more enforcement regarding punishments for lateness.

Other students requested more unlikely changes, such as making davening optional because “incorporating God into your everyday life should be a choice, not something that is forced upon us,” or a later start time.

Teachers are also brainstorming ways to improve students’ experiences at davening. Ms. Senders described her idea for a “pre-shaharit chabura” where students can choose topics to learn about to improve their own tefillot. The goal of this program would be “carving out a space where kids can elect to be there, and it’s really a self-selected group of motivated students who want to learn about a certain aspect of tefillah to help enhance their own experience.”

Ms. Gedwiser and Ms. Benus both agreed that there are challenging aspects to the davening space itself. “I don’t know if we have enough dedicated tefillah spaces,” said Ms. Benus, “I think it’s hard to do tefillah in a room that you also have math in, [or where it’s] dark, [or] where you also eat lunch. That’s a challenge of being a school in Manhattan, but the physical space where tefillah takes place can be a challenge for the atmosphere of tefillah.”

So why do we daven?

“It’s trying to model what an observant Jewish life is like,” said Ms. Gedwiser, “Learning Torah is part of that, but davening is actually the thing that more people carry into their day-to-day life later. It’s trying to live the values of the school.”

Several teachers pointed out the importance of tefillah literacy. At any point in their adult lives, Ramaz students should feel comfortable walking into a minyan anywhere in the world. “When someone graduates Ramaz they should have a familiarity with the flow of the davening such that when they walk in on Shabbat morning somewhere, or even if they don’t go back until they have to say kaddish, God forbid, we have made tefillah a familiar feeling,” said Ms. Krupka.

Just as davening is an important part of Jewish communal life, it’s also an important part of the Ramaz community. “I think that we pride ourselves at Ramaz on being a community, and this is one way that actually allows us to do that,” said Ms. Benus, “It gives us a space to talk about things that are happening in the news, it gives us a space to prioritize our connection to Israel and Judaism.”

Rabbi Schiowitz explained the importance of making davening a habit, just as people make it a habit to say thank you when someone helps them. “I wish it could be optional and everyone wanted to be there, but I think human nature is such that either they don’t want to come, or they want to come but it’s too early, and once you don’t come it’s very hard to start. Making davening part of your schedule is really good.”

Ultimately, tefillah is a mitzvah. “The goal of tefillah first and foremost is that it happens,” said Ms. Benus, “Tefillah has to happen because as a halachic Jew, you are obligated to daven three times a day. I believe that students know that, but it’s very hard to get into the headspace every single day and feel like you are able to do that. That’s a lot of Judaism—you just go through the motions until it sticks, and that’s what we’re doing, but hopefully we are able to provide a space for meaning making and a place to seek answers for questions students may have.”

Josephine Schizer has been writing for the Rampage since her freshman year and is excited to be serving as Co-Editor-in-Chief. Outside of Rampage, Josephine...