Has The Times Changed with the Times?

A Follow-Up Interview with New York Times editor Peter Applebome

Thirty years ago, news arrived with the thump of the paper being dropped at the door. Readers reconnected with the world by peeling open the paper and reading the latest news. Yesterday’s news. Old news.

Today, as the reader wipes sleep from his eyes, he groggily grabs his phone and sees President Trump’s latest tweets, reviews a multitude of blogs and posts about the latest world upheaval, watches clips on YouTube, and receives emails from the World Health Organization. In less than a minute, he is “plugged in” and remains so until he sets his phone down for the night.

So, what is the relevance of old media today? Brayden Serphos ’22 explains the logic of most students. He gets his news from Twitter, but if it is a big story, say a space launch, he confirms information with The New York Times. Serphos said, “I follow people who I consider reputable, but I definitely don’t trust everything I read on Twitter.” Adam Vasserman ’21 explained that he usually will find information on Twitter because “it is one of those amazing platforms where you can hear about current events in the moment.” Afterward, he will make sure to check the information he learns, either in The New York Times or, with regard to the virus, on Johns Hopkins University’s online tracker. Other students follow notifications of The New York Times on their phones. Sophia Kremer ’20, who reads the paper each day, said, “It is important to get notifications and learn about events while they are happening on social media. But, it is equally important to go back afterward and read a thorough article. You can’t understand a story just from five words, you need to read the background.”

On March 13, the Ramaz Upper School had the privilege of hearing the thoughts of New York Times editor, Peter Applebome, on these and other questions. Mr. Applebome, who has worked at The New York Times for more than thirty years, is the Deputy National Editor and a professor at Duke, his alma mater. During his career, he served as the Houston and Atlanta Bureau Chief, where he covered the racism embedded in the South; a reporter for the “Our Towns” column for the Metropolitan section of the paper; the author of two books; and a professor at Princeton University, Duke University, and Vanderbilt University. Mr. Applebome is most proud of winning the International Bad Hemingway Award in 1985.

During a Wednesday assembly moderated by Dr. Jon Jucovy, Mr. Applebome spoke to students about how The New York Times is adapting its reporting to the COVID-19 pandemic. As Dr. Jucovy said, Mr. Applebome is a professor and editor for The New York Times, making him the perfect candidate to “educate and inspire students, particularly those who wish to enter the field of journalism.”

To open the discussion, Dr. Jucovy, a lifelong friend of Mr. Applebome, explained that the newspaper industry changed dramatically over the last twenty years, and especially in the past few months. Mr. Applebome acknowledged this change for the purpose of relating the paper to teenagers and young adults today, referring to it as “a revolutionary adjustment, challenged by the advent of the Internet.” The Times, he argues, is relevant today because fact-checking today is critical. “It’s great that we have this blizzard of news sources, but it’s easy to be misled by the loudest voice or the best videos, or the coolest Instagram accounts, so what The Times does [when they fact check the sources] is at least as important now as it ever was.” Additionally, Mr. Applebome said that contextualizing the content today is important. It is too easy for a teenager to believe they have a full understanding of the story from reading a couple of Tweets, but it is crucial to understand the background, the implications, and what is not said, to be informed.

Mr. Applebome compared the newspaper industry to a video game. He explained, “The news is so insistent and demanding, and there is this dominant metric for viewership and eyeballs. There is no letting up, even under normal circumstances.” According to Applebome, the pandemic was the culmination of all these aspects. Recently, The Times has turned their attention toward storytelling, through a narrative form, Q&A, or presentations. There are profile stories and advice columns. Mr. Applebome said that the paper is working to crush the inaccurate stereotype of The Times being “a grey lady and a little stuffy.” In a recent piece, written by fourteen reporters, an article cataloged the pandemic from different vignettes from around the nation over a twenty-four hour period. He appreciated the work and effort of Kathrine Roseman from the Style Desk, who told the story of quarantining with siblings from the point of view of the children. Mr. Applebome said, “We go beyond hard news reporting to try to make stories as vivid and personal and compelling and accessible as we can be.”

The paper has changed in other ways as a result of the virus. There appears to be an overarching focus on the pandemic in the news, which means other important stories may be overlooked. For example, on May 22, a plane crashed in Pakistan, killing eighty travelers. While this may have been front cover news before COVID-19, in the current circumstances, it was pushed toward the back of the paper. Similarly, the Georgia shooting in May did not get the attention it deserved. According to Mr. Applebome, “the pandemic is like this fog that has enveloped everything.” However, at the same time, this pandemic also helps spotlight some stories that do not usually receive enough attention. “The one big story has so many tentacles that you can tell stories about issues like inequality and health problems in low-income communities while you’re telling the story of the pandemic. These stories are now inescapable,” Mr. Applebome explained. He described The Times as a body with different muscles. The pandemic has brought an opportunity for the paper to use all of its muscles: its storytelling muscles, its investigative muscles, its data analysis muscles.

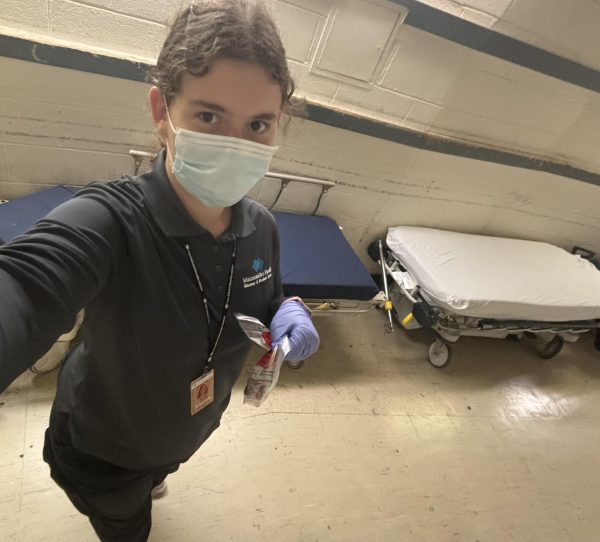

The pandemic also has challenged reporters to do their jobs in a new way. Prior to the pandemic, The Times pushed any journalist who was unsure of a situation to get on the scene as fast as possible. Now, for the most part, journalists are reporting from their kitchen tables, forcing them to “fundamentally rethink how they do their jobs,” said Mr. Applebome. Since the paper is not able to take off a day, reporters have been challenged to hear people’s voices and understand the structure of a certain area without being on the ground. Although the reporting process differs, the fact-checking process does not, as it is always mainly focused on documents obtained through a Freedom of Information request.

While many New Yorkers hate dragging themselves into the office, many editors and reporters at The Times love the building itself. Mr. Applebome described for students the “beehive of activity,” where reporters from different desks can easily exchange ideas and discuss current articles. While editors have worked hard to “simulate a lot of the serendipity” online, it can be difficult for reporters at different desks to swap ideas virtually. To interact with one another, reporters now have to purposefully call other desks; a national reporter does not simply bump into a science reporter in the elevator. The Times has held group events to recreate some sense of the missing community.

In recent years, the Jewish community has noted a left-leaning bias with regard to Israel. Gabi Potter ’20 explained, “I think there is an anti-Israel bias in The New York Times, so just reading The Times doesn’t always give the reader a full story.” At the same time, he acknowledges that there are some reporters, like Brett Stevens, who are pro-Israel and tend to support the country in his articles. Serphos explained, “No story is one-sided, so it is the responsibility of a newspaper to report on both sides and allow me to come to my own conclusions.” He feels that The Times sometimes fails to do this. When asked, many students mentioned a 2019 political cartoon of a blind President Trump being led by Prime Minister Netanyahu, who was depicted as a dog, as being anti-Israel.

According to Mr. Applebome, Jewish and Israeli issues are “the single hardest thing to cover and the single most sensitive turf.” Regardless of the article, both Palestinians and Jews argue that the paper is favoring the other side. Many Palestinians feel that the paper is “the main engine of the International Jewish Conspiracy,” and many Jews feel the paper is too left-leaning. Although he was never posted in the Middle East, Mr. Applebome once wrote about the cancellation of a Palestinian speaker in Connecticut. While he strived for balance, both sides felt attacked. “This article gave me just a small taste of how impossible [writing about Middle East issues] is,” he said.

Mr. Applebome was first inspired to pursue journalism as a career after covering the protests and chaos following Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination for the Duke Chronicle in 1968. “It was exciting to have my world engulfed in [these riots] and to have the job of making sense of it while being reportorial and analytical,” he said. After his story about how this event changed Duke was the first the Chronicle ever published in color, Mr. Applebome continued writing for newspapers and reporting all sides of an issue. He is proud to say that his first article is still hanging on The Chronicle’s bulletin board today.

Throughout his career Mr. Applebome has had many experiences that have allowed him to appreciate the value of journalism, in the form of both large projects and short articles. After writing many articles for The Times about how the South has progressed throughout history, he published a book in 1997, Dixie Rising: How the South is Shaping American Values, Politics, and Culture. Mr. Applebome writes that although New Yorkers believe they are the center of the universe, in terms of the role of religion, politics, and culture, “the South has had undue and outsized influence in American life.”

Conversely, one of Mr. Applebome’s most inspiring moments in his career was a story he wrote about Aurora, Texas. He focused on how a made-up spaceship has had everlasting effects on the town. Although at the time, Mr. Applebome was only a stringer for the paper, and, therefore, did not even receive a byline, it is one of his most memorable pieces because he appreciates the idea of “the search for truth and certainty.” While the teller of this tale has long since passed, his “ideas, once thrown out into the world, can take on a life of their own, living on in a way that would have astonished [him].” Mr. Applebome enjoys the story element of this article and enjoys imagining this story being told around a family dinner table in Aurora.

Mr. Applebome spoke about his experience speaking to high schoolers. He said, “I really like getting kids excited about journalism.” He teaches a course in universities about writing profiles about regular people and “always get a great reaction.” Mr. Applebome finds that college students are eager to absorb as much knowledge from him as they can and find his class interesting. Yet, at the same time, a journalism career has many challenges. He said that recently, “it’s a perilous job market,” as, since 2008, half of all journalists have lost their jobs. On top of that, there is a current unknown with the number of jobs that will be lost during the pandemic. Although Mr. Applebome hopes aspiring journalists have the same “satisfying career that he has had, he recognizes that it is much more difficult to accomplish in 2020 than it was when he was a young journalist.”

Mr. Applebome believes, “If you want to be a journalist, your goal should be to hit big important powerful notes and small touching personal notes.” Charles Spielfogel ’21, a Rampage staff writer, was inspired by Mr. Applebome. He said, “When I write my articles, it is easy to feel like they don’t matter or actually make a difference in my school. But, hearing from Mr. Applebome showed me that even a small story can have an everlasting impact on my school and on myself.”

Although the manner and speed in which Americans receive news are radically different than the ways their parents and grandparents received it, at its core, journalism remains the same: gathering facts, shaping a narrative, and informing the public. While today’s teenagers and young adults receive a barrage of information through alerts, Instagram, and many other sources, the current challenge, as Mr. Applebome articulated, is not accessing information, but finding reliable sources and analysis.

Rebecca Massel has been a journalist since lower school and is excited to be an editor-in-chief of The Rampage. She has been an active writer for the paper...