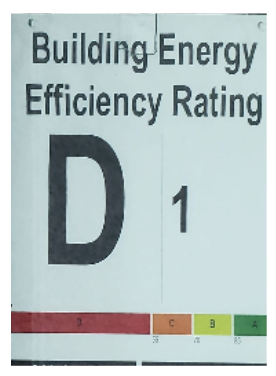

Ramaz’s Lowest Grade: The Energy Rating

The New York City Benchmarking Law requires buildings over 50,000 square feet to display their energy and water production rates by its entrance. Though the purpose of this law is to reduce the number of New York City’s greenhouse gas emissions, Ramaz has a benchmarking score of D1, the lowest score possible– other then for buildings that don’t submit their score, and buildings that are exempt.

The Energy Efficiency score is based on a scale of A to F, with A being the highest. A represents a score of 85 and higher, B is between 70 and 84, C is between 55 and 69, D is any score lower than 54, an F is for buildings that don’t submit their score, and an N is for buildings that are exempt. This rating is calculated by the Energy Star Portfolio Manager, created by the Environmental Protection Agency.

The Environmental Protection Agency is targeting buildings because buildings generate roughly 80% of New York City’s greenhouse gas emissions. Buildings over 50,000 square feet are planning to reduce their energy and water consumption by 2024 so as to not be charged a “carbon penalty.” This fine increases every five years, and it is dependent on the size of a building and how much energy and water it uses. For example, if the Ramaz Upper School does not reduce the amount of electricity and water it uses by 50% by 2024, it will be fined $37,030 each year until 2029. From 2030 to 2035, Ramaz will be fined $91,171 a year until 2035. Ramaz will then owe $117,848 from 2035 and on; this last number is a rough estimate and will probably change since 2035 is a long time away. If Ramaz does manage to reduce their energy and water consumption rates by 50% and possibly even more, then not only will they not have to pay a fine every year for the first five year cycle, but their utility cost will also go down. This can be seen as inducement for buildings to be more efficient with their energy and water usage, since their expenses will also reduce.

The Ramaz Upper School’s score is significantly lower than additional Upper East Side private schools and other Jewish day schools. While Ramaz’s energy rating is the lowest score achievable, the Yeshiva University High School for Girls of Central Queens has a score of A99. Even though the Heschel School has to pay a fine beginning in 2024 like Ramaz, their fine is only for $4,095, which is still much less than Ramaz’s penalty from 2024-2029. In comparison to Ramaz’s neighboring private schools, there is still a great gap in the amount of “carbon fines” these institutions will pay. Regis High School, Dalton, and Trevor have a high enough energy efficiency score as to not be penalized with a “carbon fine” every year for the first five year cycle from 2024-2029. The square footage of a building makes it more difficult to lower its energy and water consumption rates, and yet, these schools have managed to reduce their “carbon penalty” while being greater than twice the size of Ramaz (except for Heschel). Surely, it is still possible for Ramaz to become environmentally aware and conscious, just like these schools.

Hesham Nouh, the Director of Facilities of the Ramaz School, has answers for many of these concerns. Nouh said, “A low energy efficiency score is to be expected considering the building was designed in the 1970s – a time when mechanical and lighting systems were highly inefficient. That being said, Ramaz is committed to gradually upgrade outdated mechanical equipment and retrofit inefficient lighting systems when possible.”

By looking at Ramaz’s letter grade without its percentage, Ramaz’s energy rating could be considered average, considering that most of New York Citys’ buildings do not have great energy efficiency scores; out of all 40,000 who had received their grades, half had earned Ds. Even New York City’s most prominent buildings haven’t been doing well. An article from the Curbed, which is part of New York Magazine, selected 50 of New York City’s most iconic buildings, and 28 received Ds. Perhaps most New York Citys’ buildings began this challenge with a rough start since this benchmarking law was put into place very recently, and buildings haven’t had enough time to reduce their electricity and water usage.

An energy consultant used public data about Ramaz’s energy usage to gain an understanding of the upper school’s resource consumption. He had cited buildings twice as large as Ramaz that use less energy and explained that “It’s difficult for a building to shed that much electricity. [Ramaz is] using at least double the amount of electricity than they should.” The specialist reasoned that the waste might stem from old and inefficient appliances and that switching them could remedy the issue, but he couldn’t be certain with the limited information he had. He said that “there are many energy service companies out there that offer a guaranteed savings contract” and that “budget is not a reason to avoid these upgrades.”

There are plenty of ways that a building can better optimize its energy usage. The two largest users of electricity are climate control and lighting. A solution to the excess amount of heating and cooling would be to improve the building’s insulation. Adding extra insulation would reduce heat flow between the outside and inside. Another viable method is to restrict the hours that climate control can be on. For instance, only using climate control during school hours, even if people are still in the building. The other major user of electricity is lighting. Lights are on in a room all day whether the room is being used or not. Adding motion detector sensors to the light switches would only allow the lights to be on while someone is using them. Ultimately, a large part of the issue may be from inefficient appliances that are outdated. Replacing heating and cooling units and lightbulbs may have an enormous effect on Ramaz’s energy usage.

Ramaz’s energy efficiency rating is the lowest awardable score due to the overwhelming waste of electricity. Students feel that the building’s energy consumption needs immediate reform because of the environmental repercussions. On top of “going green,” there is a huge financial benefit of making the building more eco-friendly because New York City plans on charging Ramaz hundreds of thousands of dollars if the consumption stays the same. There are countless solutions to reducing the amount of wasted electricity. Time is of the essence: the sooner Ramaz addresses the energy building’s energy crisis, the better. Making these changes are a win-win. Ramaz can help the environment and avoid huge fines. Does Ramaz want this grade as part of their average?