Mask Mandate: Enforcement of the “Grey Area”

The ability of the administration to enforce school rules can be much more intricate than expected. There are some school rules that are extremely clear cut: they are easily enforced, clearly understood, and widely accepted by everyone in the community. However, not all school rules are so black and white. In fact, there is a wide grey area of rules that exist in our Ramaz community. School rules like these tend to be much blurrier in the eyes of the student body, and enforcing them is an everlasting challenge that the administration continues to face.

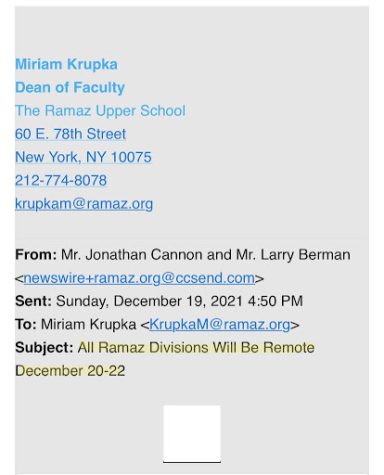

When it comes to the school’s grading system, the rules are obvious to the Ramaz community: receiving a 95 will give you an A, an 85 will give you a B, etc. With the grading system, there’s no ambiguity — everyone knows the rules, and the majority will adhere to them. A student who averages an 85 won’t ask a teacher why they received a B on their report card, because the answer is obvious: according to the school rule, an 85 gives you a B. Similarly, the school’s policy regarding lateness is clearly understood by the students. At the start of each year, the school’s strike and detention system is reinforced by the administration and reintroduced to the students. If a student taps in late to school, he or she can expect a strike — two more, and he or she will get detention. Two more detentions, and he or she will earn Social Probation. This consistent, simple system of action and consequence is just as easily enforceable by the administration as it is understandable by the students. Ms. Krupka explains that when it comes to these types of “black and white rules, there’s an immediate consequence. Black and white rules are when it is so obvious that breaking a rule is a poor choice, and the exact result of doing so will be an unfavorable outcome for the student.”

Not all Ramaz policies are so easily enforced. Take the dress code, for example. Most girls in Ramaz are well aware of the fact that skirts are required to approach the knee, but many girls do not follow this rule. Sophie Schwartz 23’ explains that she knows that her skirt length is technically not in accordance with the school rule, but she has “never actually been told to change her skirt.” Most boys are well aware of the kippah mandate, requiring kippot to be worn at all times during school, yet some boys’ kippot find their way from the students’ heads and into their pockets. While the Ramaz community clearly understands the expectations of the dress code itself, not all follow it, since the administration has a hard time enforcing this more ambiguous policy.

Similarly, the mask mandate is a very complex and difficult policy to enforce. Walking through the hallways of Ramaz, one can notice students whose masks are secured tightly above their nose, drooping beneath their nose, hanging beneath their chin, or whose masks are nowhere to be found.

One can notice some teachers reprimanding students for wearing their masks incorrectly, and others who are not wearing masks themselves. Clearly, the enforcement of the mask mandate is a nearly impossible task. The question is why. Why is it that certain school rules are more easily enforced than others? What causes students to view certain rules as being categorized in this “grey area” as opposed to being so called “black and white?”

The answers to these questions boil down to a couple of defining factors in terms of how rules are sculpted and enforced, including consistency, prioritization, consequences, and accessibility. To begin with, a school policy which is consistently reinforced every school year will be taken much more seriously by the students than one that is not. Not only has Ramaz’s lateness policy remained consistent within the past couple of years, but the administration’s strictness level in terms of enforcing it has also remained constant. Never has the administration randomly decided to test out how the school year would go if strikes were not accounted for. And when it comes to exceptions to the lateness rule, the school has also remained consistent — only students who arrive late due to commuting on a school bus are exempt from receiving a strike. The same thing goes for the grading system: the school has always been consistent in its method of calculating students’ semester grades. Never has a student’s overall average of 85 given him/her a B one year, but a C the next year. Due to their clear-cut consistency, these policies, along with many others, have become like muscle memory to the student body.

In addition, the way in which the school prioritizes certain policies can also cause them to be more or less accepted by the Ramaz community. The Ramaz administration takes its grading system very seriously, ensuring that teachers properly account for all their students’ scores before report cards come out. The administration’s prioritization of grades causes both the teachers and students to prioritize them as well.

Additionally, a clear and proper system of action and consequence will cause any school policy to be much more feared and respected within the Ramaz community. Take the lateness policy, for example. Every student knows that the consequence of tapping in late to school is a strike. Knowing this, students try to avoid receiving a strike, and ultimately detention, by coming to school on time. By fearing the consequence of breaking a school policy, students are much more likely to obey it. “When it comes to rules in the ambiguous grey area, students are not going to receive an immediate consequence for their actions,” says Ms. Krupka.

And finally, the only logical way for the administration to enforce any policy is by having proper access to any given student’s response and adherence to the rule. In other words, the administration must be able to physically see and account for those who do or do not follow a given rule. This is why ambiguous rules such as masks and dress code are physically difficult to enforce — because there is no attendance sheet or grade point average that can account for each student whose skirt is too short or whose mask is below their nose.